Mel asked a perceptive question near the end of class, which I’ll paraphrase here:

If, by definition, a commitment to social justice involves making practical

changes to the world, then why devote time to theoretical

debates, i.e., to intellectual exercises that don’t lead — at least not directly — to action?

One response to that question goes something like this: While pursuing social justice certainly involves taking action on urgent and very concrete issues, it isn’t only, or even primarily, about “fixing” what’s wrong with our community in light of our accepted ideals. Rather, it’s about inventing new and different ideals. It’s about discovering new and different ways of understanding ourselves and the world that we share. It’s about radically re-imagining what our community can and should be. In other words, the work of social justice isn’t only reparative. It’s also a profoundly

imaginative act — one that demands not only a capacity for nitty-gritty, real world engagement, but also the full range of our critical and creative powers. So while it may be true that theorizing becomes an arid academic exercise when divorced from practical action, it’s also true that forms of action that don’t aim to radically transform how we

think aren’t very likely to change the world much, either.

|

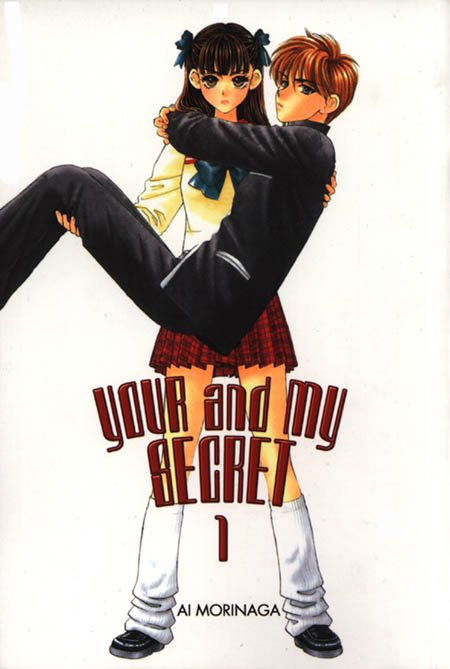

Judith Peck, Veiled Identity, from the show

Original Position, inspired by John Rawls's

Theory of Justice.

|

For some time now, feminism has grappled very directly with both sides of this conundrum. On the one hand, gender injustice has been embedded so deeply and for so long in our cultural DNA that to try to imagine a world without it involves rethinking all of the core ideas by which we understand that world. On the other hand, feminists are keenly aware that ideas take on meaning only by virtue of how they’re

embodied.

So, in our next class, we’ll have a different kind of debate (hence the scare quotes in this post's title). Rather than assigning propositions for the teams to affirm or deny, I’m going to ask each team to develop an original argument in response to a question. Then, as a group, we’ll see if we can’t generate a third, still more original argument by putting the first two into dialogue.

Here’s the question:

If working for social justice means both building a better world by imagining it anew and imagining a new world through the process of building it, then what should an education in social justice be?

Please be really concrete in your arguments. For example: How should classes be conducted (if at all)? Where? About what? With whom? According to what (if any) rules and involving what (if any) roles? What should we be doing outside of school (if we even want to make the distinction between "inside" and "outside")? How could we make this new notion of education real? And so on and so forth. In short, take this as an opportunity to re-imagine what a social justice education can and should be, and take responsibility for figuring out how to embody that idea in reality.

To assist you, I’ve posted two pieces of feminist writing in the Content folder on

Blackboard, each of which explores what it means to imagine and to work to realize a new and different social world: Susan Moller Okun’s “Justice as Fairness: For Whom?” and Cherríe L. Moraga’s “From Inside the First World” (the foreword to an anthology titled

This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color). Neither is about education per se, but both pursue provocative and potentially inspiring lines of argument very much relevant to questions of education; so please draw on them as you develop your own ideas.